TRI Martin Poetry

I write the things I wasn’t allowed to say out loud.

And I write them the way they arrived:

crooked,

uninvited,

hard to look at straight.

A fan scraping algae so you can sit up again

Sockets holding their own petri dishes of whatever someone left in you

A mudcake, a pack of Alpine Ultralites, and a cask of Lambrusco

Poking the eyes of a snail you’re dating

Cunt as the place where you soothed someone else’s nervous system

Furby Eyes, Dating Guys and Mouldy Face

Grief that smells like something you should have thrown out days ago

Soy-sauce fish sparking a councillor conversation

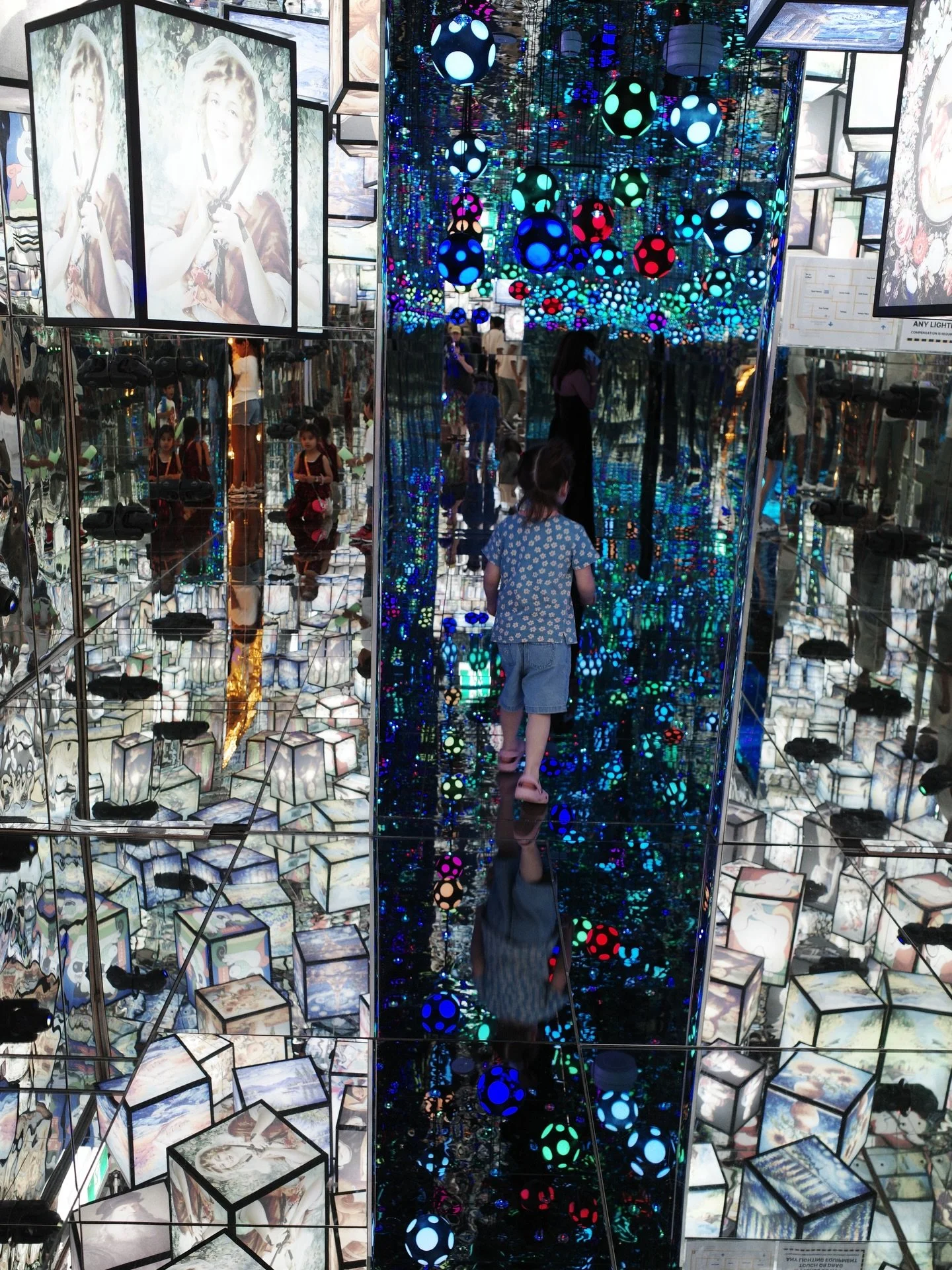

Glowstick body adjustments

New Tinder bios > LOL

Eau de Kitchen Sink

Gangly gross feet before you die

Sweatshirts flogged like 17th century punishments.

Eurythmics

A new national anthem

I live in the debris that floated up when the silence cracked.

My Dad asked “Is everything auto-biographical”

“Yes” I replied.

“Hmm, maybe best I don’t read it then”

Everything here is true.

And not the polite version, the version that allowed my muted voice to sing.

How I’d describe my poems

They say something bleak

and somehow leave the lift of an Enya chorus in their wake.

Their metaphors don’t arrive —

they lurk in doorways and turn their heads when you look at them.

They’re the rare place

where humiliation and humour agree to carpool in silence.

They read with the emotional accuracy

of someone who can hear dust settling.

They feel like all the silent versions of yourself

finally teamed up to write a burn book.

They behave like intrusive thoughts

that decided to pay rent and rearrange your drawers.

They stay rooted in the everyday

until the everyday starts warping.

They deliver the shock

of being gut-punched by a sentence spoken casually.

They can place a Coles mudcake on a table

and expose a whole family system in one motion.

They describe the unbearable so plainly

you nod as though it’s a shared secret.

They stay with you,

like an ex you have to co-parent with.

“I went to school with a cornflake stuck to my lip” – the first writing tip ever sent to me.

One strange little line from Paul Jennings lodged itself into my memory and quietly became the thread running through my non-linear path back to writing.

Writing always came naturally, until high school didn’t.

A system built for sameness couldn’t make sense of a weird, neurodivergent, metaphor-heavy-loner kid.

Support went elsewhere. Doubt moved in.

My new identity became my internal joke:

“illiterate, wanting to write literature”.

Said like a punchline, swallowed like truth.

I carried its heaviness through life like evidence.

I still wrote, but only in the “not real” ways, according to the educated.

“Just a blogger,” the journalists would laugh, as if that explained why I didn’t belong.

I’d leave embarrassed, like the cornflake really had been stuck to my lip.

The cornflake line always resurfaced.

Cornflake Girl was the first “real” poem I wrote as an adult —

thirty years after receiving that advice.

The writing wasn’t impressive, but it was intrusive—

it forced me to hear a part of myself I’d spent years trying to mute.

It stuck.

And so I began to take writing— again.

As if the middle finger had finally found its prose.

I’m Tri, a Melbourne poet who has, at last, metaphorically gone to school with a cornflake stuck to her lip —

and this time, I’m keeping it there.

where to find mE

other info

-

info at trimartin dot com dot au

or @poet.tri on Insta

-

I’m keeping most of my work offline while I draft my debut book and send poems out into the world.

Until then, updates live on Instagram: @poet.tri.

-

My work is written on Wurundjeri Country in Healesville. I pay my respect to Wurundjeri Elders past and present, and acknowledge that this land always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

-

Ocean Vuong — Time Is a Mother

Hera Lindsay Bird — Hera Lindsay Bird

Jenny Zhang — My Baby First Birthday

Evelyn Araluen — The Rot

Lynn Melnick — Landscape with Sex and Violence